Preview

Description

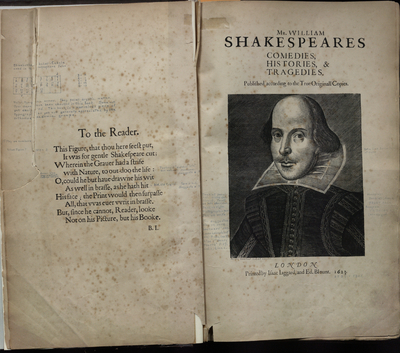

Original title page of the First Folio, showing a portrait of William Shakespeare, reproduced in the SUNY Buffalo State First Folio facsimile from 1866.

Marginalia are the notes and comments left in the margins of books. Marginalia has been a feature of the physical book throughout history and can be anything from a smiley face to indicate a favorite passage to elaborate literary criticism taking up all the blank space on a page.

In the SUNY Buffalo State First Folio facsimile, the marginalia throughout the book makes the copy unique. We know very little for sure about the person who wrote the marginalia (called a marginaliast), but close readings of the words s/he left behind can reveal a lot about his or her identity.

One thing we do know is that the marginaliast was a staunch Baconian. Baconians are readers and scholars who believe that Francis Bacon (a contemporary English statesman) wrote the plays that are commonly attributed to William Shakespeare. The theory was first proposed by William Henry Smith in 1854 in his pamphlet, “Was Lord Bacon the Author of Shakespeare’s Plays?” and gained increasing popularity throughout the nineteenth century.

Baconians doubted that someone with Shakespeare’s background (that is, the son of an illiterate tradesman from a rural village) would be able to write plays like “Hamlet” and “The Tempest.” Therefore, Baconians searched for someone more likely to have written plays of such literary merit and decided it could only be Francis Bacon.

To prove their belief that Bacon wrote Shakespeare’s plays, Baconians have used elaborate codes, conspiracy theories, and logical leaps. On this page of the SUNY Buffalo State First Folio facsimile, the Baconian marginaliast provides a numerological key that s/he believes unlocks secret messages proving Bacon’s authorship throughout the First Folio.

The idea of secret, coded clues left by Bacon among “his” plays – commonly called Baconian cryptology – was first promoted by U.S. Congressman Ignatius L. Donnelly in 1888 in his book The Great Cryptogram: Francis Bacon’s Cipher in the So-Called Shakespeare Plays. In his book, Donnelly professed himself troubled by one aspect of Baconian theory: “Would the writer of such immortal works sever them from himself and cast them off forever?”[1]

After stumbling upon a book of cryptography, Donnelly believed he had found the answer to his troubles, writing, “The key here turned, for the first time, in the secret wars of the Cipher, will yet unlock a vast history…and tell a mighty story of…the most gifted human being that ever dwelt upon the earth.”[2] He did not mean William Shakespeare.

After Donnelly’s book was published, Baconian cryptology took off as Baconians searched the First Folio for the words “Francis, Bacon, Nicholas, Bacon, and such combinations of Shake and speare or Shakes and peer, as would make the word Shakespeare.”[3] Donnelly himself recommended Day & Son’s facsimile of the First Folio specifically, marking it as necessary reading for Baconians.[4]

So what does this tell us about our marginaliast? Most likely, s/he was writing after 1888. Much of the marginalia in the SUNY Buffalo State First Folio facsimile is inspired by Donnelly’s theories, including the secret code shown on this page and used throughout the facsimile.

Keywords

William Shakespeare, First Folio, marginalia, book history, Francis Bacon, cryptography, codes

Comments

[1] Ignatius L. Donnelly, The Great Cryptogram: Francis Bacon’s Cipher in the So-Called Shakespeare Plays (Chicago, New York and London: R.S. Peale Company, 1888), 505.

[2] Ibid., vi.

[3] Ibid., 516.

[4] Ibid., 547.

< Previous Exhibit Page

Next Exhibit Page >