Preview

Description

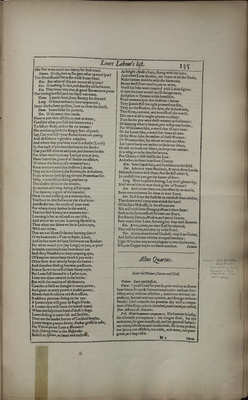

One page of 'Love’s Labour's Lost' in the SUNY Buffalo State facsimile of William Shakespeare's First Folio from 1866.

On this page, the marginaliast in the SUNY Buffalo State First Folio facsimile notes that the fifth act of “Love’s Labour’s Lost” is mislabeled as the fourth act (“Act Quartus” should read “Act Quintus”). While noticing this type of misnumbering suggests that the marginaliast was paying close attention to what s/he was reading, appearances may be deceiving.

While we are now accustomed to purchasing books with each page already separated from the others, in the nineteenth century, books were sold with “unopened” pages, or with pages still connected to each other.[1] In the printing process, multiple pages would be printed on large sheets of paper which were then folded down to the size of the book and bound, leaving pages still folded and connected to each other, or “unopened.”[2] Readers would have to cut open each page to read it as they went along, which can be useful for modern scholars seeking to learn something about a specific reader’s habits.

In the case of the SUNY Buffalo State First Folio facsimile, most of the pages remain unopened and only a few pages were ever opened (and thus likely read). These pages are scattered throughout the facsimile, with some appearing the middle of plays and others stretching through entire sections. The opened pages seem strategic to a certain extent, suggesting a reader who knew specifically what s/he was looking for rather than someone engaged in a detailed study of the text, page by page.

Why was this? Because the marginaliast appears to have cribbed a great deal of his or her insights from other sources. As has been discussed on previous pages, the marginaliast drew his or her ciphers, acrostics, and theories from a variety of already-published Baconian books, including William Stone Booth’s Some Acrostic Signatures of Francis Bacon, Walter Conrad Arensberg’s The Cryptography of Shakespeare, and Frank Woodward’s Francis Bacon’s Cipher Signatures. Some of the marginalia in the SUNY Buffalo State First Folio facsimile is nearly verbatim transcription of these other books’ Baconian theories, which explains how the marginaliast knew exactly where to look in the book – and which pages to cut.

Keywords

William Shakespeare, First Folio, marginalia, book history

Comments

[1] “Unopened,” Biblio.com, accessed April 23, 2016, http://www.biblio.com/book_collecting_terminology/unopened-89.html.

[2] Ibid.

< Previous Exhibit Page

Next Exhibit Page >