-

Global change drivers synergize with the negative impacts of non-native invasive ants on native seed-dispersing ants

Robert Warren

Non-native species invasion, habitat fragmentation and climate change individually impose negative impacts on natural systems, but their synergistic effects may do more harm than the sum of their parts. We examined the combined effects of these global change drivers by studying the impacts of experimental warming on seed-dispersing forest ant nesting and foraging in the Southeastern U.S. to determine if warming and forest fragmentation facilitated non-native ant invasion effects on native ants. Spring ant phenology and activities were monitored for two years (2019-2020) at weekly bait stations and in artificial nest occupancy. We found that, when combined, forest edge habitat and experimental warming favored invasive non-native ant frequency, but the experimental warming alone did not appear to facilitate non-native ant incursion into forested habitat. We did find, however, that experimental warming exacerbated the negative effects of non-native ants on native ant foraging. Moreover, fragmented edge habitat strongly limited native forest ant foraging and experimental warming increased the negative effects of non-native ant invaders on native ants. Ultimately, the non-native ants displaced native seed-dispersing ants from artificial nests, and the displacement progressively increasing with greater experimental warming. Our results suggest that global change drivers such as warming, habitat fragmentation and species invasion imposed negative impacts individually, but their combined effects were worse than the sum of their parts. Moreover, our results indicate that predicting species reactions to global change poses great challenges given that the strongest impacts were the non-additive effects.

-

Laurentian Great Lakes warming threatens northern fruit belt refugia

Robert Warren

Climate refugia are anomalous ‘pockets’ of spatially or temporally disjunct environmental conditions that buffer distinct flora and fauna against prevailing climatic conditions. Physiographic landscape features, such as large water bodies, can create these micro-to-macro-scale terrestrial habitats, such as the prevailing westerly winds across the Laurentian Great Lakes that create relatively cooler leeward conditions in spring and relatively warmer leeward conditions in autumn. The leeward Great Lakes climate effects create a refugia (popularly known as a ‘fruit belt’) favorable for fruit-bearing trees and shrubs. This fruit belt refugia owes its existence to seasonal inversions whereby spring cooling prevents early flower budding that leaves fruit trees susceptible to late spring killing frosts, and autumn warming prevents early killing frosts. With global climate change, however, warmer summers and milder winters, and corresponding warmer waters, might erode the leeward delaying effect on spring flowering, creating a paradoxical situation in which warming increases the risk of frost damage to plants. We evaluated the success of regional agricultural in the Great Lakes fruit belt to test our hypothesis that warmer spring climate (and concomitant warmer lake waters) correspond with degraded fruit production. We also examined long-term trends in Great Lakes climate conditions. We found that the cold-sensitive fruit tree (apple, grape, peach and cherry) refugia was destabilized by relatively warmer springs. Moreover, we found several indicators that lake waters are warming across the Great Lakes, which portends negative consequences for agricultural and natural plant communities in the Great Lakes region and in similar ‘fruit belt’ refugia worldwide.

-

Myrmecochorous plants and their ant seed dispersers through successional stages in temperate cove forests

Robert Warren, Mary Schultz, James Costa, Beverly Collins, and Mark Bradford

Anthropogenic disturbance can decrease woodland diversity in the species-rich herbaceous layer of eastern deciduous forests, and ant-dispersed (myrmecochorous) plants may be particularly affected due to their limited ability to re-colonize secondary forests. Consequently, we predicted that myrmecochorous plants and their keystone seed-dispersing ants would increase with time since last disturbance, as reflected by young, middle or mature forest successional stage. Specifically, we hypothesized that myrmecochore abundance and richness would be relatively lowest in the youngest forests, moderate in middle-aged forests and highest in mature forests. We also hypothesized that experimentally introducing ant bait in a regular pattern, as might be expected from intact species-rich myrmecochore communities, would elicit greater ant foraging interest than intermittent baiting, as might be expected in recently disturbed depauperate myrmecochore communities. We found the highest myrmecochore plant abundance in mature forests, but we found the same for herbaceous plants overall. Moreover, regular and intermittent bait offerings elicited similar overall ant responses. The observational results suggested that myrmecochorous plants respond to forest successional stage as do other woodland plants, and our experimental results suggest that disrupted seed delivery by myrmecochores did not affect Aphaenogaster abundance or foraging behavior. As such, the myrmecochore communities studied here appeared as resilient as other woodland herbs, and seed-dispersing ants did not appear dependent on myrmecochore plant communities. Indeed, given the relatively high myrmecochore richness and abundance across our study sites, forest type (e.g., rich cove forest) might better predict myrmecochore success than successional stage.

-

Pennuto et al. Goby migration data

Christopher Pennuto

These are data used for a manuscript on round goby nearshore/offshore migration behavior in Lake Ontario. The file is an Excel format that includes raw data for number of fish observed, their sizes, size of gobies in sturgeon guts.

-

Non-native Microstegium vimineum populations collapse with fungal leaf spot disease outbreak

Robert Warren

Abstract

Non-native plants may meet little resistance in the novel range if they leave their biological enemies at home. As a result, species invasion can be rapid and appear unlimited. However, with time, organisms may acquire novel enemies in the novel range, or home-range enemies also may colonize the novel range. For plants, several authors have suggested that enemy release may give way to enemy acquisition in which pathogens accumulate and suppresses non-native plants. The ‘naturalization’ that occurs with acquired enemies may take decades to develop, yet most species invasion research lasts less than 4 years, and data tracking plant invasion before and after the appearance of pathogens are rare. Microstegium vimineum is an Asian grass that has invaded deciduous forest habitats in the southern Midwestern and Southeastern U.S. and is currently expanding in the Northeastern U.S. We recorded widespread expansions in M. populations in North Carolina and Georgia (U.S.) between 2009-2011 but noticed that a fungal pathogen (indicated by leaf lesions; Bipolaris sp.) appeared on several of the populations in 2011. In 2019, we re-sampled these populations to determine whether the appearance of the fungal pathogen corresponded with a suppression of M. vimineum expansion. We found the once-expanding M. vimineum populations in retreat in 2019, and the plant population contractions were greater (and seed production lesser) where the fungal leaf spot disease was most extensive. These results suggest that enemy acquisition suppressed an active non-native plant invasion. We also found that where M. vimineum populations declined (or disappeared) native plants appeared to fill in the gap. Hence, whereby exotic species may gain advantage in novel habitat with the loss of their native-range pathogens, with longer time spans, enemy release may give way to enemy acquisition and native populations may recover if they are immune to the pathogens.

-

Regional-scale environmental resistance to non-native ant invasion

Robert Warren

A successful invasion of novel habitat requires that non-native organisms overcome native abiotic and biotic resistance. Non-native species can overcome abiotic resistance if they arrive with traits well-suited for the invaded habitat or if they can rapidly acclimate or adapt. Non-native species may co-exist with native species if they require novel, underused resources or if they can out-compete similar native species. We investigated abiotic and biotic resistance to the progression of a Brachyponera chinensis invasion in the southeastern U.S. relative to the dominant native woodland ant (Aphaenogaster). We used observational data from long-term plots along the elevation gradient of the Southern Appalachian Mountain escarpment to investigate the patterns of B. chinensis invasion, and we used physiological thermal tolerance, aggression assays and stable isotope analysis to determine whether abiotic or biotic factors explained B. chinensis invasion. We found that B. chinensis exhibited an inflexible and relatively poor ability to tolerate cold temperatures, which corresponded with limited success at higher elevations in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Though we found native ant resistance to B. chinensis invasion, it paled in comparison to the invasive ant’s ability to form huge, cooperating supercolonies that eventually eliminated the native ant. Without biotic resistance, susceptible native species may only be protected if they can tolerate abiotic conditions that the invasive species cannot. For Aphaenogaster species, high elevations and northern latitudes beyond B. chinensis’ cold tolerance may be their only refuge.

-

Non-native ant invader displaces native ants but facilitates non-predatory invertebrates

Robert Warren and Madeson C. Goodman

Many invasive ants, such as the European fire ant (Myrmica rubra), are particularly successful invaders due to their ability to form multi-nest, multi-queen 'supercolonies' that appear to displace native invertebrates in invaded regions. Myrmica rubra has invaded many areas in the Northeastern United States, including Western New York. Myrmica rubra invasion corresponds with decreases in native invertebrates, particularly ants, an effect which may be attributable to direct displacement, or because M. rubra prefers habitat unsuitable for native ants. We surveyed Western New York parklands to investigate native ant and non-ant invertebrate abundance in M. rubra-invaded and uninvaded areas. We then tested these observations with an ant pesticide treatment targeting M. rubra to investigate the direct impacts of M. rubra on the native ant and invertebrate community. A consistent, negative relationship was found between M. rubra and native ants in both the observational and experimental research, and native ant species only appeared in the pesticide-treated plots (with reduced M. rubra abundance). These data strongly suggest that M. rubra actively displaces the native ants with invasion instead of segregating by habitat. Myrmica rubra effects on non-ant invertebrates appeared more nuanced, however, in both the observational and experimental research. The absence or removal of M. rubra corresponded with decreased predatory invertebrate populations and increased non-predatory invertebrates. It appears that M. rubra has altered invertebrate communities in Western New York. Native invertebrate communities may be able to rebound with time, but our data suggest native recovery unlikely without management intervention.

-

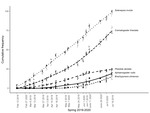

Interacting effects of urbanization and coastal gradients on ant thermal responses

Robert Warren

Urban-to-rural gradients intersect with other, often unmeasured, environmental gradients that may influence or even supersede species responses. Here we use coastal-to-interior and urban-rural gradients to investigate woodland ant response (physiological thermal tolerance, community structure and spring phenology) to two overlapping thermal gradients, the Great Lakes (Erie and Ontario) and the Buffalo, NY urban center (USA). Woodland ant physiological and behavioral responses, and community responses, shifted along the coastal-to-interior and urban-rural gradients, but they were generally best explained by lake effects (though urban ants tolerated higher temperatures than rural ants). The relatively colder spring temperatures in coastal areas (as compared to inland) corresponded with higher physiological cold tolerance in the ants, even though the coastal areas are annually warmer. The coastal spring temperatures also influenced ant phenology so that, in a warm year, the coastal ants began foraging considerably earlier than inland ants, likely due to their lower physiological cold tolerance. Ant community responses also shifted with proximity to the lakes and urban areas, but those changes appeared more linked with land use than climate. These results suggest that species responses to urbanization gradients may be influenced, or even superseded, by the impacts of proximate large water bodies. Our results suggested that spring coldness nearer the Great Lakes may select for cold tolerance in ants (despite that the coastal areas are relatively warmer annually), whereas urbanization selected for greater heat tolerance.

-

Release from intraspecific competition promotes dominance of a non-native invader

Robert Warren

Species can coexist through equalizing (similar fitness abilities) and stabilizing (unique niche requirements) mechanisms – assuming that intraspecific competition imposes more limitation than interspecific competition. Non-native species often de-stabilize coexistence, suggesting that they bring either a fitness advantage or a distinct niche requirement. We tested whether greater fitness or unique niche requirements best explained a successful North American invasion by the European Myrmica rubra ant. North American invaded-range M. rubra aggressively sting and occur in enormous numbers (suggesting a fitness advantage), yet our study site has a history of anthropogenic disturbance that might favor M. rubra (suggesting a unique niche). We compared M. rubra to native ants, principally the dominant North American woodland ant Aphaenogaster picea, using physiological health (lipids and size), monthly bait station surveys and aggression assays to assess fitness abilities, and we used nest surveys and isotope analysis to assess niche characteristics. We confirmed the field observations with laboratory experiments that tested colony aggression (direct competition) and food retrieval (indirect competition). In both the observational and experimental investigations, we found little evidence of M. rubra interspecific competitive advantage (aggression or food retrieval) or niche differentiation. Instead, M. rubra violated the basic assumption of coexistence theory: intraspecific competition consistently was less than interspecific competition. Freed up from the costs and limitations of territorial competition, some non-native species may outcompete native species by not competing with themselves. This 'friendly release' from intraspecific competition provides an ecological mechanism for some successful invasions.

-

Do novel weapons that degrade mycorrhizal mutualisms promote species invasion?

Robert Warren, Phil Pinzone, Daniel L. Potts, and Gary Pettibone

Non-native plants often dominate novel habitats where they did not co-evolve with the local species. The novel weapons hypothesis suggests that non-native plants bring competitive traits against which native species have not adapted defenses. Novel weapons may directly affect plant competitors by inhibiting germination or growth, or indirectly by attacking competitor plant mutualists (degraded mutualisms hypothesis). Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) and European buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) are widespread plant invaders that produce potent secondary compounds that negatively impact plant competitors. We tested whether their impacts were consistent with a direct effect on the tree seedlings (novel weapons) or an indirect attack via degradation of seedling mutualists (degraded mutualism). We compared recruitment and performance using three Ulmus congeners and three Betula congeners treated with allelopathic root macerations from allopatric and sympatric ranges. Moreover, given that the allelopathic species would be less likely to degrade their own fungal symbiont types, we used arbuscular mycorrhizal (AMF) and ectomycorrhizal (ECM) tree species to investigate the effects of F. japonica (no mycorrhizal association) and Rhamnus cathartica (ECM association) on the different fungal types. We also investigated the effects of F. japonica and R. cathartica exudates on AMF root colonization. Our results suggest that the allelopathic plant exudates impact seedlings directly by inhibiting germination and indirectly by degrading fungal mutualists. Novel weapons inhibited allopatric seedling germination but sympatric species were unaffected. However, seedling survivorship and growth appeared more dependent on mycorrhizal fungi, and mycorrhizal fungi were inhibited by allopatric species. These results suggest that novel weapons promote plant invasion by directly inhibiting allopatric competitor germination and indirectly by inhibiting mutualist fungi necessary for growth and survival.

-

A systematic review of context bias in invasion biology

Robert Warren

The language that scientists use to frame biological invasions may reveal inherent bias - including how data are interpreted. A frequent critique of invasion biology is the use of value-laden language that may indicate context bias. Here we use a systematic study of language and interpretation in papers drawn from invasion biology to evaluate whether there is a link between the framing of papers and the interpretation of results. We also examine any trends in context bias in biological invasion research. We examined 651 peer-reviewed invasive species competition studies and implemented a rigorous systematic review to examine bias in the presentation and interpretation of native and invasive competition in invasion biology. We predicted that bias in the presentation of invasive species is increasing, as suggested by several authors, and that bias against invasive species would result in misinterpreting their competitive dominance in correlational observational studies compared to causative experimental studies. We indeed found evidence of bias in the presentation and interpretation of invasive species research; authors often introduced research with invasive species in a negative context and study results were interpreted against invasive species more in correlational studies. However, we also found a distinct decrease in those biases since the mid-2000s. Given that there have been several waves of criticism from scientists both inside and outside invasion biology, our evidence suggests that the subdiscipline has somewhat self-corrected apparent biases.

-

Nest-mediated seed dispersal

Robert Warren

Many plant seeds travel on the wind and through animal ingestion or adhesion; however, an overlooked dispersal mode may lurk within those dispersal modes. Viable seeds may remain attached or embedded within materials birds gather for nest building. Our objective was to determine if birds inadvertently transport seeds when they forage for plant materials to build, insulate and line nests. We also hypothesized that nest-mediated dispersal might be particularly useful for plants that use mating systems with self-fertilized seeds embedded in their stems. We gathered bird nests in temperate forests and fields in eastern North America and germinated the plant material. We also employed experimental nest boxes and performed nest dissections to rule out airborne and fecal contamination. We found that birds collect plant stem material and mud for nest construction and inadvertently transport the seeds contained within. Experimental nest boxes indicated that bird nests were not passive recipients of seeds (e.g., carried on wind), but arrived in the materials used to construct nests. We germinated 144 plant species from the nests of 23 bird species. A large proportion of the nest germinants were graminoids containing self-fertilized seeds inside stems – suggesting that nest dispersal may be an adaptive benefit of closed mating systems. Avian nest building appears a dispersal pathway for hundreds of plant species, including many non-native species, at distances of at least 100-200 m. We propose a new plant dispersal guild to describe this phenomenon, caliochory (calio = Greek for nest).

Printing is not supported at the primary Gallery Thumbnail page. Please first navigate to a specific Image before printing.